CEEPR Working Paper

2025-20

Sophia A. E. Spitzer, Katja Pelzer, Anton Bauer, and Maximilian J. Blaschke

Fusion power has long been hailed as a transformative technology capable of delivering virtually limitless, carbon-free electricity (Armstrong et al. 2024; Takeda et al. 2023; Schwartz et al. 2023; Nicholas et al. 2021). Its expected attributes — clean baseload generation, high energy density, and siting flexibility — make it attractive to the ambitious global decarbonization agenda. Yet repeated delays and the so-called “fusion constant,” the perception that fusion is always thirty years away (Takeda and Pearson 2019; Ball 2021), have made its commercialization success and timing highly uncertain.

This study evaluates fusion’s prospective role in a future energy system through a two-stage approach. First, we implement fusion plants in PyPSA-Eur, an open-source, sector-coupled model of the European energy system with three-hour temporal resolution and a 39-node spatial network (Brown et al. 2024; Victoria et al. 2022; Victoria et al. 2020; Neumann et al. 2023). The model simulates a cost-optimal capacity mix from 2030 to 2100 under varying assumptions about fusion’s commercialization date (2035 vs. 2050), overnight capital costs, and diffusion constraints. Second, a probabilistic evaluation framework translates modeled system cost savings into an Anticipated Commercialization Probability (ACP), a measure of the likelihood investors implicitly assign to fusion’s success based on observed investment flows.

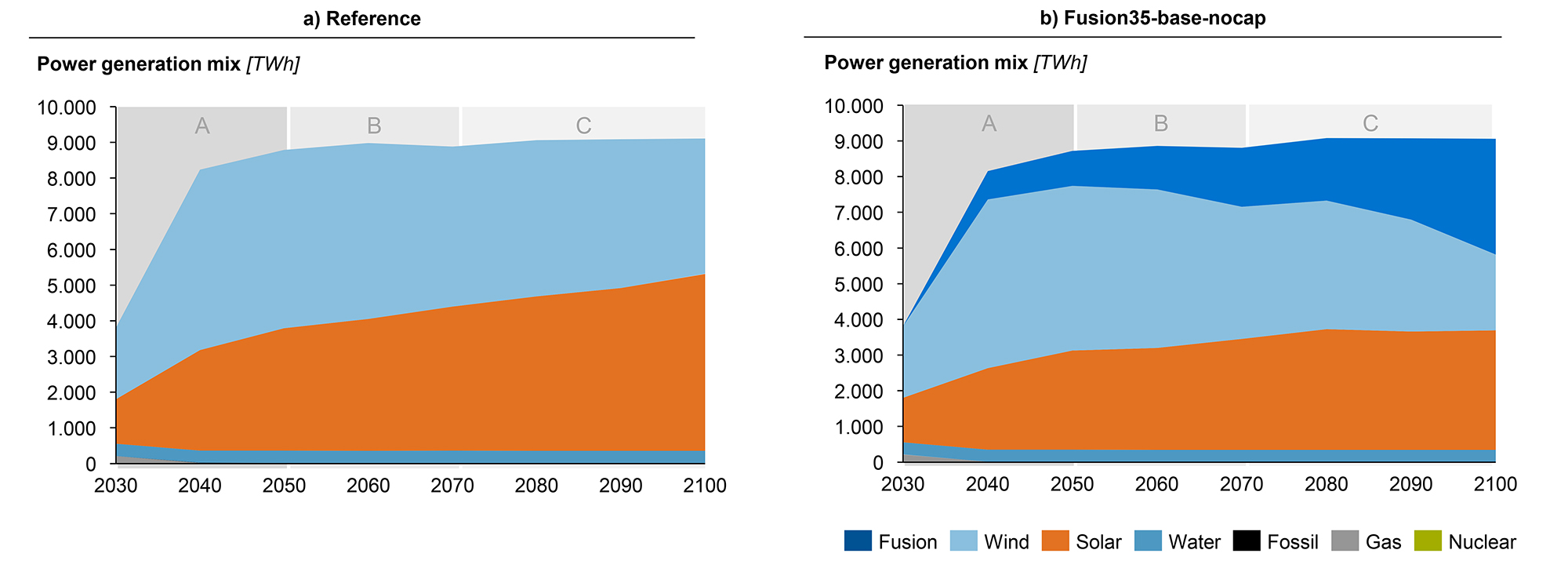

The modeling reveals three characteristic phases of fusion deployment (see Figure 1).

Diffusion phase (2035–2050): Fusion grows in parallel with increasing electricity demand during the energy transition.

Replacement phase (2050–2070): A second wave of fusion growth coincides with the end-of-life replacement of renewables installed during the pre-2040 high-growth phase. This shift is primarily driven by the phase-out of wind capacity, which has become less competitive due to its comparatively lower learning rates compared to solar PV.

Saturation phase (after 2070): Fusion’s relative advantage diminishes as cost reductions slow. The technology reaches a saturation point, where fusion’s learning rate unlocks new energy generation potential only under favorable cost trajectories.

Under low-cost assumptions (< 4,000 USD2020/kWel), fusion could supply up to 30 % of European electricity by 2100 and reduce cumulative system costs by nearly EUR 2 trillion (discounted to 2020). Crucially, these savings arise less from cheap generation per se than from avoided storage and renewable capacity: As a baseload source, each gigawatt of fusion can displace several gigawatts of variable renewables, cutting storage needs, grid expansion, and balancing services. Even with only a 10 % capacity share, fusion’s high utilization enables it to deliver roughly one-third of total generation while reducing long-distance transmission needs by up to 20 % and hydrogen transport by 45 %.

Capital costs emerge as the single strongest driver of fusion’s market share and system value. Low overnight capital costs enable fusion to scale to double-digit capacity shares even if commercialization is delayed, while high costs render the technology marginal regardless of timing or build-out limits. Timing remains critical, particularly for the economic value. A delay from 2035 to 2050 reduces the discounted system savings by more than half, even when long-run generation shares stay sizable.

By comparing modeled system benefits to cumulative European public and private investments (EUR 42 billion by 2035; EUR 76 billion by 2050), we further infer anticipated success probabilities below 20 % for a 2035 market entry. This gap between large theoretical value and modest investment reflects a high-risk/high-reward paradox typical of breakthrough technologies: uncertainty suppresses funding, which in turn limits the likelihood of success.

Policy implications are twofold. First, accelerating cost reductions — e.g., through modular reactor designs, standardized licensing, or milestone-based incentives — is critical for timely deployment. Second, current investment levels appear inconsistent with the societal value that fusion could provide. Without stronger public support or new financing mechanisms, Europe risks underinvesting in a technology that could lower long-term energy costs and enhance energy sovereignty.

Figure 1. Evolution of Europe’s energy generation mix with (Fusion35-base-nocap) and without (Reference) fusion.

Note: The reference scenario follows PyPSA-Eur assumptions extrapolated to 2100. The fusion scenario assumes fusion availability from 2035 under baseline cost assumptions and without capacity deployment constraints.