CEEPR Working Paper

2022-017, November 2022

Jonas Martin, Emil Dimanchev, and Anne Neumann

Additional climate policy efforts are needed for “hard-to-abate” sectors such as heavy-duty trucking, shipping, and aviation, in order for governments to deliver on net zero emission targets and limit global warming within 1.5°C. While electrification plays a primary role in 1.5°C and 2°C decarbonization pathways for light vehicles, other sectors – aviation, parts of heavy-duty road transport, and maritime transport – may be impractical or very difficult to electrify, even in the long term. One abatement strategy in these sectors is the replacement of fossil fuels with renewable hydrogen fuels.

To design climate policy, governments rely on estimates for the costs of alternative abatement options. Abatement costs allow decision makers to understand how alternative solutions compare, how much a policy will cost, or what options can be implemented within a given budget. However, it is currently unclear how economically feasible different hydrogen fuels are as abatement options in the trucking, shipping, and aviation sectors. Martin, Neumann, and Ødegård (2022) showed that the hydrogen fuels are far from cost competitive on a total cost of ownership basis.

This paper estimates the abatement costs of replacing fossil fuel use in freight trucking, shipping, and aviation with renewable hydrogen fuels. Specifically, this work focuses on long-haul trucking, short-sea shipping and short-haul aviation. We use a detailed bottom-up technoeconomic cost model. The model’s high level of detail allows us to compare abatement across sectors (trucking, shipping, and aviation), fuels (hydrogen, ammonia and e-fuels), and across time (2020, 2035, 2050). Our estimates across these dimensions are internally consistent and allow inter-sector and inter-fuel comparisons.

We quantify abatement costs by calculating the Levelized Cost of Carbon Abatement (LCCA) across sectors and fuels. Our LCCA estimates can be interpreted as long-run marginal abatement costs (covering a horizon long enough to allow changes in the capital stock). From a policy perspective, our LCCAs represent the carbon price required for an abatement action to break even, or the carbon price at which an abatement action may be assumed to be taken. This paper also explores how subsidies on different parts of the hydrogen value chain can contribute to reducing clean transport costs. Finally, we estimate how different combinations of carbon pricing and hydrogen subsidies may impact the competitiveness of clean transport.

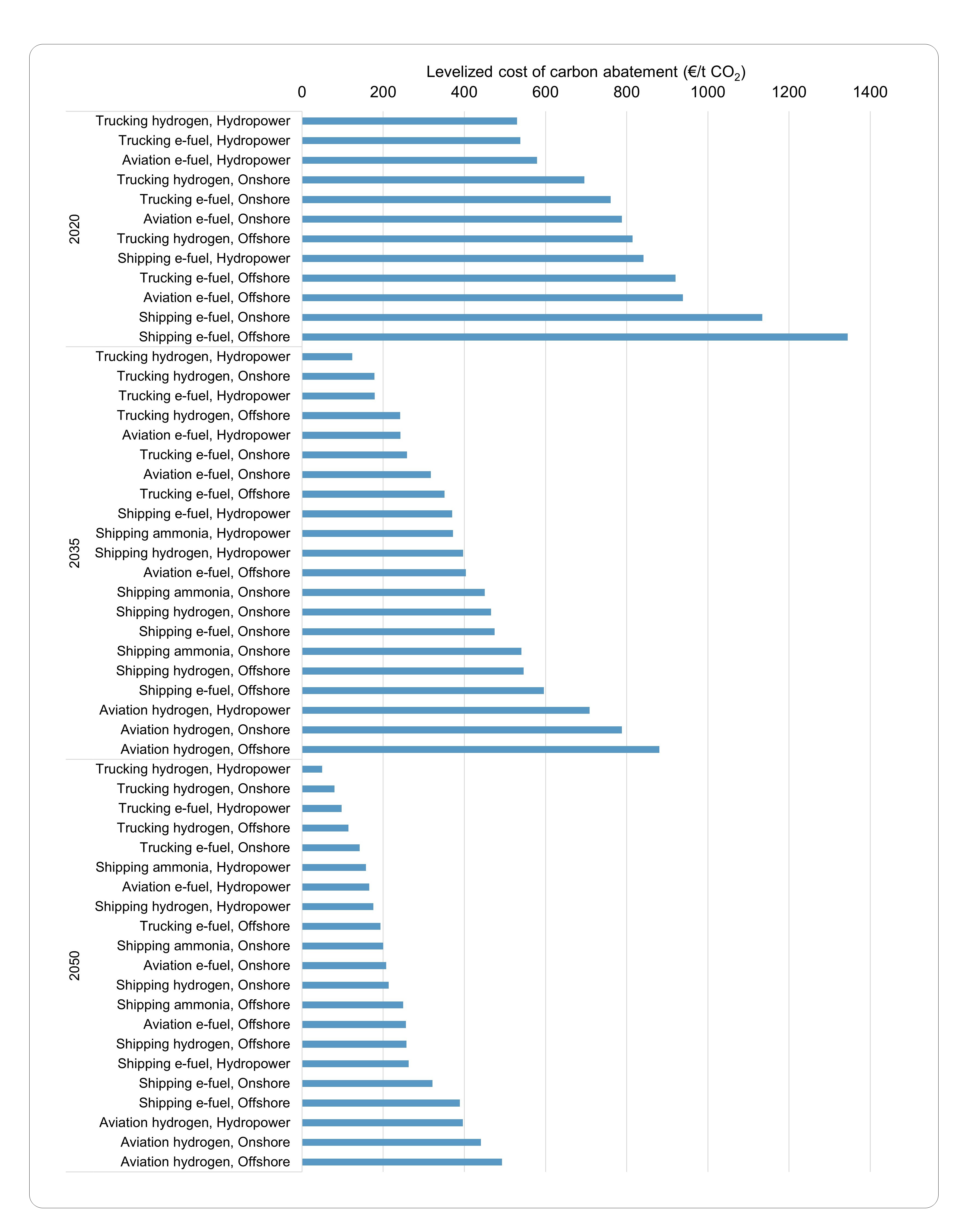

We estimate abatement costs for hydrogen fuels of €530-1,345/tCO2 in 2020. Comparing across sectors and electricity sources, we find the lowest abatement costs in 2020 in the trucking sector, equal to €530/tCO2 for hydrogen and €760/tCO2 for e-fuel, both produced from hydropower. Trucking remains the lowest cost abatement out of the options we studied also in the following years until 2050 (if electricity comes from hydro or onshore wind). This is due to the fact that the trucking sector exhibits the lowest cost premium on a €/tkm basis and the relative emission intensity of diesel-powered trucks. This implies that trucking could serve as an early niche market for the development of hydrogen technologies that could drive cost reductions in electrolysis, having in mind the fast developments in battery truck technology.

Turning to technological differences within sectors, abatement cost for e-fuels in trucking are higher than for hydrogen because a comparably low vehicle Capex cannot offset higher fuel cost and a lower engine efficiency. In shipping, from 2030 and beyond, ammonia exhibits the lowest abatement cost, starting with €538/tCO2 in 2030 and reaching €200/tCO2 in 2050. In aviation, e-fuel use, which costs €788/tCO2 and reaching €208/tCO2 in 2020, is a cheaper abatement option compared to hydrogen all the way to 2050.

For policy, this analysis suggests that if carbon prices remain at current levels (€84/tCO2 in Europe in the first half of 2022 and generally lower in other jurisdictions), renewable hydrogen fuels will require additional governmental incentives. Based on our results, such incentives appear necessary at multiple points on the value chain. We show that subsidizing the €/kg cost of hydrogen has a relatively large impact out of the interventions we tested, which suggests that innovation policy targeting hydrogen costs could be seen as a focal point of future hydrogen policy.

In 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives proposed a tax credit for hydrogen fuel equivalent to a subsidy of $3/kg. Our results show that with current costs, hydrogen use in trucking would still require a high carbon price or other incentives to be cost-competitive. However, potential cost declines of components and processes across the value chains alleviate the need for subsidies. By 2035, the cost model we use estimates a potential hydrogen cost of €3/kg. At that point, either a carbon price of

€200/tCO2, or a lower carbon price paired with a hydrogen subsidy could be enough to incentivize hydrogen adoption.

E-fuel costs are more sensitive than other hydrogen fuels to fuel production subsidies.

References

Martin J, Neumann A, and Ødegård A (2022) “Sustainable Hydrogen Fuels versus Fossil Fuels for Trucking, Shipping and Aviation: A Dynamic Cost Model” MIT CEEPR Working Paper 2022-010, July 2022.

Martin J, Dimanchev E, Neumann A, (2022), “Carbon Abatement Costs for Hydrogen Fuels in Hard-to-Abate Transport Sectors and Potential Climate Policy Mixes,” MIT CEEPR Working Paper 2022-017, November 2022.