Scott Burger, Jose Pablo Chaves-Ãvila, Carlos Batlle, and Ignacio J. Pérez-Arriaga

Electricity systems are currently facing significant changes as a result of the deployment of information and communication technologies (ICTs), power electronics, and distributed energy resources (e.g., gas-fired distributed generation, solar PV, small wind farms, electric vehicles, energy storage, and demand response). Given the small scale of these technologies, many industry stakeholders claim that aggregators can create economic value by enabling DERs to provide these services at scale.

Citing the untapped value of aggregators, regulators and policy makers in both Europe and the United States are debating the role of aggregators. In Europe’s liberalized retail markets, the debate is centered around the functioning of retail markets, the ability of retailers to deliver desired levels of consumer engagement and value-added services, and the value or disvalue of superimposing third party aggregators over these retailers. On the other hand, new independent aggregators are highly active in U.S. markets, and stakeholders are attempting to design market rules to ensure these aggregators flourish due to true value creation as opposed to regulatory arbitrage. This debate has implications for a wide range of questions, such as: should the power system accommodate many aggregators or only one centralized aggregator? Who can or should be an aggregator (transmission and distribution system operators, retailers, third parties, etc.)? What market design elements may need to be adapted or adopted to accommodate DERs? What is the “best feasible level of unbundling”?

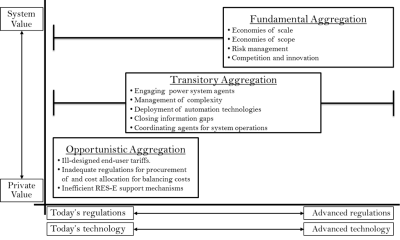

In a recent MIT CEEPR Working Paper, a team of authors from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Comillas Pontifical University review the economic and power systems literature to clarify ongoing debates about the value of aggregators, establishing an economically grounded “rational template” with which to analyze the role of aggregators in power systems. Based on their review, the authors argue that, in a hypothetical world with “perfect” information, economically rational agents, and “perfect” regulations, aggregators will only create value by capitalizing on economies of scale and scope and by managing risks (these are termed “fundamental values” by the authors). They further note that maximizing the benefits of these sources of value could lead to a single, centralized aggregator, which might harm other power system objectives such as competition, agent engagement, and innovation; thus, the role of aggregators would be determined by analyzing the tradeoffs between fundamental values and the value of competition. Recognizing that such a hypothetical, perfect world is far from current realities, they identify “transitory” values of aggregation that may exist as power system technologies and regulations advance. Finally, they identify a number of regulations and market designs that create “opportunistic” aggregations; these opportunistic aggregations impair as opposed to enhance power system economic efficiency. Figure 1‑1, at the end of this article, summarizes these findings.

Fundamental value stems from factors inherent to the act of aggregation itself. While regulation and policy may influence whether or not this value is captured and by whom, the value itself is regulation, policy, and agent-independent. In the context of the power system, aggregation may create fundamental value through capitalizing on economies of scale and scope and by mitigating uncertainty. These fundamental values give the aggregator characteristics of an economic club, and, if considering only economic factors, may lead to a market structure with a monopolistic aggregator, harming competition. Furthermore, competition amongst aggregators may create value through driving agent engagement (enabling the participation and optimization of DERs), and potentially mitigating market power. Where sufficient data does not exist to balance the described value streams, regulators and policy makers should reduce entry barriers for new aggregators, allowing market forces to provide the efficient balance of competing or monopoly aggregators.

Aggregators may create value to the power system transitions from the near future scenario to the reference future scenario. Transitory value is not necessarily inherent to aggregation, but may be unlocked by aggregation. Transitory value, by definition, may exist only for a period of time until superior solutions emerge. In their analysis, the authors highlight that transitory value comes from closing information gaps (i.e. related to price signals, complexity of power system) as well as agent engagement. Closing information gaps may have very large impacts in the near term. Indeed, today’s aggregators (both third party aggregators and retailers) pass on price signals to end consumers, enabling more efficient energy consumption. Further, these aggregators are providing automating technologies that have the potential to increase network utilization, decrease total costs, and increase consumer engagement in the near and long term.

Finally, opportunistic aggregation may emerge as a response to regulatory flaws. This opportunism may create private value without increasing the economic efficiency of the system; furthermore, this opportunism may restrict competition, especially for small agents. The study’s authors highlight a number of regulations that create opportunistic aggregations – i.e. aggregations that harm overall system efficiency. Rules related to the procurement of balancing services (i.e. penalties beyond imbalance payments and symmetric bidding requirements), rules regarding the allocation of balancing costs to agents (i.e. allowing portfolio balancing and using dual imbalance pricing), and inconsistent locational price signals and network charges all create opportunities for regulatory arbitrage and opportunistic aggregations.

Where aggregation creates fundamental or transitory value, regulators or policy makers may want to take steps to remove barriers to its realization or to encourage it outright. However, where aggregation only leverages opportunistic value or regulatory arbitrage, regulations should be modified (unless this fact is explicitly acknowledged and desired as a form of subsidy). The foregoing review thus serves to highlight the tradeoffs between the values that aggregators may provide to the system.

Figure 1: Value of aggregators based on technology and regulatory contexts.